Chris Rix - Passing Down

|

August 5, 2002

Passing Down

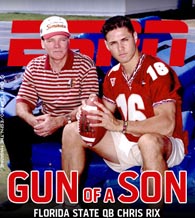

ESPN The Magazine The proud father wears a Florida State cap, a Florida State golf shirt, a lug nut-sized Gator Bowl ring given to him by his famous son, the Florida State quarterback. He pulls a packet of photos from his back pants pocket. "I brought a couple of pictures," says Chris Rix Sr. He leans across the restaurant table, close enough that you can smell stale smoke breath, close enough that you can see his eyes misting up as he stares at the memories. There he is at a 1981 company picnic with his newborn son ... with his beautiful bikini-clad wife and tiny Junior in Newport, R.I. ... with his young family in Central Park, not far from their old place on East 72nd Street. Back then he was a stockbroker on Wall Street; she managed the Windows of the World restaurant at the World Trade Center.

*** Theda Mendoza drew her last breath 13 years ago, with Chris Sr. at her side and 7-year-old Chris Jr. waiting just outside her hospital room. A day earlier she had watched from her bed as Junior happily played with a balsa glider outside the hospital window. That was before the cancer overwhelmed her, before Senior noticed her beginning to slip away. Hold on," he told her, "I'm going to get Chris." He raced from the room and found his son in the gift shop. Then came a page on the PA system: "Mr. Rix, please come immediately." So he ran through the halls, his son trying to keep up, and didn't stop until he was at his wife's bedside. "I closed her eyes," he says, struggling to speak. "I brought Chris in." Another long silence. "That was that." A country club waiter chooses this exact moment to cheerfully offer iced tea refills. Senior lowers his head, pinches the bridge of his nose and uses a knuckle to wipe away a tear. The waiter skulks to a corner of the dining room. Chris Rix Sr. can't quite let go of that night at the hospital -- and why should he? But he also can't quite let go of that 7-year-old son, the one who has grown up to throw more than balsa airplanes into the afternoon sky. Senior has devoted his life to Junior. He moved him from New York to Seattle to Los Angeles and finally to Rancho Santa Margarita, 52 miles south of LA. He raised him, read Bible stories to him every night, prayed with him, pushed him, supported him, nagged him, imposed his will on him, loved him. Always loved him. Perhaps too much. "When Chris was young, we had those little electric race cars that would go on the plastic track," he says. "You'd have those little speed controls. If you went too fast that car would go flipping off the track in a heartbeat. Too slow, the other guy would whip your butt and you'd have to catch up. I think the art of parenting is finding out how much torque to put on that control." Senior has never been shy about torquing up the control. He can't help himself. It's about never getting your butt whipped, about never having to catch up. If that means nudging your son toward Florida State and Bobby Bowden, who promised to treat Junior like his own son, then you nudge. If it means critiquing your kid while watching an FSU replay telecast together, so be it. If it means standing behind the Seminoles bench during last season's loss at Florida and yelling at Junior, "Run the ball more!" then you yell. Junior blanches when reminded of the Florida incident. He didn't think anyone knew: "I told him to leave me alone. I told him, 'Dad, I don't need you to be on me during the game.' But that's just him being Dad. It's been hard for him to let go of the leash. It's like, 'All right, Dad, you really need to take a step back.'" It was no accident that Junior took exactly one unofficial recruiting trip (to FSU) before committing to the Seminoles a year before signing day. Or that he never even visited another school. Or that he ran for FSU student body vice president. Or that as a freshman he became the first FSU football player in years to enroll in Army ROTC ("It is sort of unusual," says Rix's Military Science instructor, Major Dave Storey), just so he could learn more about leadership and discipline. Senior's fingerprints, with Junior's blessings, were all over those decisions. But Junior can be just as calculating. Shortly before the start of 2001 spring practice, he broke some news to Bowden. "Well," he said, "I broke up with my girlfriend." "Why?" said Bowden. "I want to put everything on football." Rix became the first redshirt freshman quarterback to start a season for Bowden in 26 years, succeeding Heisman Trophy winner Chris Weinke, a dropback statue whose play was as steady as the Tomahawk Chop. But by mid-October the Seminoles were 3-2, out of the national championship race and grumbling about "Hollywood" Rix and his macho high school style of play. Protected by the hands-off green practice jersey worn by FSU QBs, Rix would anger the defenders by squirming for extra yardage. Then someone popped him one day, and that was that. Some of the upperclassmen said he ran too much. He turned the ball over too much. He talked too much. "He probably didn't trust his teammates as much as he should," says wide receiver Anquan Boldin. "When the team was going bad at the beginning, people were pointing the finger at him." Rix never pointed back. But he knew he was close to losing his teammates, to say nothing of his starting job. Still, the more Rix asserted himself, the more he alienated his teammates. "Some players say he was too cocky," says guard Montrae Holland. "Some players didn't like him. He just needed to grow up, you know?" Bowden knew what was happening. Everyone in the program did. "The thing we lacked last year was leadership," says Bowden. "The best leader on our football team was Chris Rix. That's the good news: He's a great leader. The bad news: They ain't going to accept a freshman." Rix arrived at Burt Reynolds Hall in the summer of 2000 and is the only remaining player from his incoming class who still lives there. He doesn't want an off-campus apartment; he likes living by himself right next to the Seminoles' practice facility. Rix has a 60-inch TV, and his DVDs are arranged in alphabetical order. His favorites: The Ten Commandments (seen it 20 times), Gladiator (30 times) and Varsity Blues (50 times). He doesn't wear jeans. His closet, full of pressed shirts and pants, looks as if it's been organized by a valet. His '87 T-top Mustang with the 18-inch chromies is parked out front, and you can usually find R&B or P&W (praise and worship) music in its stereo. In short, Rix is polite, neat, religious, athletic, confident. But not altogether tight with his team. "I think there is a difference between a California quarterback and one from Georgia or Florida," says Bowden. "Those kids out in California, their demeanor is different. It's pretty outgoing, pretty confident. Here in our part of the country, they're more subdued, more patient." Rix was the anti-Weinke -- impulsive, impatient and, at times, clueless. And he was always immutably confident in his 4.4 speed and Favre-like arm.

Makes them tighter than most players and coaches. Then again, Bowden was the same way about former FSU running back Warrick Dunn, whose mother, a Baton Rouge police officer, was killed in the line of duty. "I have a soft spot for any player on my team who doesn't have a mother, who doesn't have a father," Bowden says. "But yeah, I do think I have a soft spot for Chris. I think I try to cover up a void in that area. I'm crazy about him. I just hope I'm doing him right. Yet, I don't want to show partiality. He's earned everything he's got." Six games into last season, with Rix and the Noles still struggling, Bowden began working true freshman Adrian McPherson, Florida's Mr. Football, into the rotation. FSU beat Virginia using both quarterbacks and was about to face undefeated Maryland a week later. "There were doubts around the Maryland game," says Holland. "You knew he had to perform. If he messed up, then maybe he lost his job for the rest of the season." Bowden got a phone call that week. It was Rix Sr. "Let him play the fourth quarter," said Senior. "Quarterbacks are made in the fourth quarter. That's where the great quarterbacks are made." Bowden promised nothing. FSU trailed 14-0 in the second quarter, and Rix was on the bench, knocked silly by Maryland LB E.J. Henderson. Rix had completed just 2 of 6 attempts for 24 yards. To make matters worse, Rix Sr. came down to field level and yelled, "Relax!" "He didn't need to tell me that," says Junior. "E.J. Henderson took care of that. I thought he broke my neck. It's the hardest I've ever been hit." But something happened when Rix re-entered the game with 6:04 remaining in the first half. He didn't have that hyperventilating-in-the-brown-paper-bag look to him. Instead, he completed 13 of his next 18 passes for 326 yards and five touchdowns in a 52-31 victory against a Terps team that wouldn't lose another regular-season game. "I had the best game of my life," Rix says. That was the day his teammates stopped looking at him as the pretty boy from California. "When we won that game -- and how we won it -- that's when I figured, okay, we got ourselves a quarterback," says Holland. He wasn't the only one. By season's end, Rix ranked eighth in the nation in passing efficiency. He had completed 58% of his attempts for 2,734 yards and 24 touchdowns, and made it obvious who was the Seminoles' most important player. "Without Chris," says RB Nick Maddox, "well, I'm not going to say we wouldn't have won any games, but his athletic ability helped us out a lot." Rix may never fit in. But he doesn't have to become one of the guys to command their respect. "This spring I was talking more in the huddle," he says. "And instead of looking at the ground, they were looking me in the eye." Rix's appreciation for history extends beyond the trials of last year. Rix Sr. got Junior's Gator Bowl ring, but Bowden got the post-bowl bear hug. "That one's for you," he told Bowden after the win against Virginia Tech. He knows he could be the quarterback who helps Bowden pass Bear Bryant's victory total (he's tied) and perhaps even surpass Joe Paterno's mark (he trails by four). He knows he might be the last starting quarterback Bowden, 72, ever coaches. And he knows he'd be lost without those office visits. Junior isn't the only one to defer to Bowden. Rix's old man gushes like an endorsement ad when he talks about the coach. Senior still calls Bowden every two or three months, but the numbers are down from the early days. It's almost as if there's been a transfer of parental power -- no small gesture on Senior's part. He trusts Bowden. And he knows Junior trusts him too. That's why this odd little triangle of personalities works so well. *** August drills are still more than a month away, but Senior and

Junior already feel the heat as they play a round of golf at an

Irvine, Calif., muni. Senior, with cigarettes nearby and brewskis

on ice in a plastic bag, is wearing his usual FSU clothing ensemble.

Everything is going fine until Senior gets an attack of the Butch

Harmons. Junior glares back, ignores the advice ... and tops the drive about 30 yards. Senior shakes his head. Kids. Meanwhile, you can almost hear Junior counting the seconds until he's anywhere but near his old man. This is when you think the viscosity of their relationship is breaking down like cheap 10W-30. But it isn't. It can't -- not after what they've been through. A couple of weeks later Junior is back in Tallahassee, alone with his alphabetized DVDs and folded clothes ... and he misses his dad. He's 7 years old again. They talk on the phone that night until the wee hours. They talk about football, FSU, Bowden, God, the past, the present, the future. Senior remarried several years ago. Junior wants to move on too, but not necessarily with his old man attached to his hip bone. "Dad, relax," he says through the phone. "You've done a great job getting me here. Now let me take care of it. Concentrate on your marriage. Enjoy life. Just enjoy this." You know what Senior says? "Okay, son. Okay." Imagine that. The old man has let up on the control. |

They had a little summer cabana

out on Long Island. Family lived nearby. Father and son played baseball

on the sand, football under the street lights -- the curbs were

out of bounds. Senior made sure Junior always beat out the throw

for the winning run, always eluded the last tackler for the winning

touchdown, always ended the game with a smile on his face. Even

then he was big with the life lessons. "I thought once he started

playing sports, he'd learn to experience defeat," says Senior. He

pauses before handing over the final photo. There he is with Junior

on Mother's Day 2001. Look hard and you can see his wife's name

on the grave marker.

They had a little summer cabana

out on Long Island. Family lived nearby. Father and son played baseball

on the sand, football under the street lights -- the curbs were

out of bounds. Senior made sure Junior always beat out the throw

for the winning run, always eluded the last tackler for the winning

touchdown, always ended the game with a smile on his face. Even

then he was big with the life lessons. "I thought once he started

playing sports, he'd learn to experience defeat," says Senior. He

pauses before handing over the final photo. There he is with Junior

on Mother's Day 2001. Look hard and you can see his wife's name

on the grave marker. Bowden has made good on his promise

to Senior to treat Junior as if he were his own son. But Bowden's

method of parenting differs from Senior's. Bowden isn't one to torque

the control. Rix has a standing invitation to stop by Bowden's office

any day, any time. Bobby slaps him on the back as Rix takes the

field and says, "Hey, how you doin', boy? Have a great practice!"

They pray together. (Instead of dotting the i's in his name, Rix

uses a cross.) They give testimonies at Tallahassee churches together.

"Makes us pretty tight, doesn't it?" says Bowden.

Bowden has made good on his promise

to Senior to treat Junior as if he were his own son. But Bowden's

method of parenting differs from Senior's. Bowden isn't one to torque

the control. Rix has a standing invitation to stop by Bowden's office

any day, any time. Bobby slaps him on the back as Rix takes the

field and says, "Hey, how you doin', boy? Have a great practice!"

They pray together. (Instead of dotting the i's in his name, Rix

uses a cross.) They give testimonies at Tallahassee churches together.

"Makes us pretty tight, doesn't it?" says Bowden.