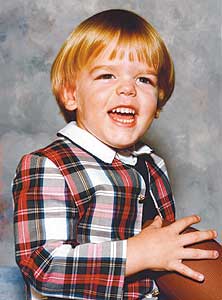

Carson Palmer - USC

Home-grown talent By TODD HARMONSON ORLANDO, FLA. Destiny seemed to drive Carson Palmer to the eve of the biggest day of his life, but determination deserves more of the credit. Sure, USC's quarterback looked the part of the natural athlete from birth at 10 1/2 pounds and 24 inches, and his success in everything from the country club golf tournament he won at age 3 1/2 to skiing and basketball only confirmed that he had gifts few possess. He has been a quarterback from his first day on a football field, he learned from one of the nation's ultimate quarterback gurus, and his Laguna Hills bedroom featured a lithograph of USC's four Heisman Trophy winners and their autographs. The evidence seems clear: Palmer was destined to be a finalist for the Heisman Trophy and maybe even win college football's most prestigious prize Saturday in New York. But plenty of players had the talent and the tools, followed the perfect path and fell far short. Palmer had something that set him apart, something that helped him through the troubled times and eventually kept him grounded even when the hype ventured toward a high that only a Heisman hopeful can experience. "I wouldn't be here without my family and everything they've done for me," he said. Of course, that's what every well-trained athlete is supposed to say. It sounds classy and makes him seem a little sappy and sentimental, but too often it is delivered with all the sincerity of a politician's promise. He has to say it, even if he doesn't mean it. But Palmer does, and a look at his life before the spotlight became his constant companion shows exactly why. He experienced a rather normal upbringing, even if it was a tad nomadic, but he also learned a lesson about what parents will do for their children. From infancy, he was the child who always had a ball of some sort in his hands, even if it meant crawling around his parents' Fresno home to get a ball even though his legs were in corrective casts to fix a problem with his bones. When Palmer's father, Bill, and his sister, Jennifer, played a round of golf at a Westlake Village club, Palmer begged his mother to let him tag along. Eventually, Danna Palmer relented and let her 3-year-old son walk the course with a putter in his hands. "By the end, he was playing," she said. "And he was so happy that I let him go. He said, 'You're the best mommy in the world. Thank you so much.' " He took to skiing like a seasoned veteran when the Palmers moved to Colorado Springs, and he was thrilled to play in a tackle football league as a fifth-grader when they returned for a second stint in Fresno. "We moved around a lot, but it really was a normal childhood," said Palmer, who also has two brothers, Robert and Jordan, a freshman quarterback at Texas-El Paso. "I was really into sports, and I always loved football." His talent was obvious by the time he was in seventh grade and the Palmers had arrived in Orange County. He played in a Junior All-American league and quickly won the starting quarterback job, and Bill Palmer realized his son needed more guidance. He looked in a high school sports magazine and found an ad for a quarterback coach and gave Bob Johnson a call. "He said he usually only worked with high schoolers, but he was willing to take a look at Carson," Bill Palmer said. "When we got to a workout they had, I think he was surprised by how big Carson already was and what he could do." And Palmer's development got a huge boost from his work with Johnson, who coaches at Mission Viejo High and is the father of former USC quarterback Rob Johnson and ex-UCLA quarterback Bret Johnson. A friendship also developed between Johnson and Bill Palmer, to the point where Johnson called Santa Margarita High coach Jim Hartigan to tell him what he was about to get in Palmer. "Carson was a great leader for us," Hartigan said. "He was a good kid who really was well-liked. I wouldn't say he was the most popular kid in school, but everyone liked him." Johnson, who used Palmer as a counselor at his Elite 11 camp last summer, also made some detailed inquiries into schools in southern Connecticut when the Palmers planned to move again in 1996. "I got a great job in New York and we realized we wanted to live in Connecticut and I would commute," said Bill Palmer, who is involved in financial planning. "We took the boys (Carson and Jordan) back there and they just hated it." Still, the Palmers went ahead with their plans. They allowed Carson to choose what high school he wanted to attend and they bought a home in the neighborhood. Palmer met with the football coaches and even went to a football camp with his new team at Boston College. "When I went to pick him up, I hoped he'd be excited about it and gung-ho about the move," Bill Palmer said. "He was miserable. He said, 'Dad, I'm the biggest guy on the team and they're going to make me an offensive lineman. And the linemen don't even lift. They just sit around and eat candy.' " Said Carson: "It was horrible. Football was so different there. Nobody cared. Plus, I really liked California." Bill and Danna Palmer knew they could force the issue and simply tell their sons they were moving, but they ultimately chose to keep them in Orange County. The Connecticut house? "We never stayed a night in it," Bill Palmer said. "We got it one day and put a 'For Sale' sign in the front yard the next." Bill Palmer, however, still had the great job opportunity and he decided with his wife that he would commute so their family could stay put and he could work. That lasted nearly four years, first from Los Angeles to New York and then to Boston. The family took two cars to church on Sundays so Bill could leave from there to the airport, and he returned Fridays and often went directly to Santa Margarita football games. He couldn't do much about Palmer's Wednesday night basketball games, but those were the only contests he missed. "That's when I realized what a great man my father is," Palmer said. "He sacrificed so much so that Jordan and I wouldn't have to move. He was away from his wife and kids all the time, living in an apartment instead of our house. That wasn't a marriage. But he did what he felt he had to do. "It was tough on him and my mom, but they did it for us. It really was amazing." Many athletes have experienced more hardship than Palmer. He realizes that when he looks at his USC teammates who have come from broken homes or struggled with a parent's long illness and death. Most people who see Palmer assume he is the typical Californian who lives near the beach and never wants for anything. But even if he didn't experience poverty, he still has the perspective that comes from pain and perseverance. Perhaps he would have gotten to this point anyway. Maybe talent would have triumphed even without the help of his family. But destiny got a lot of help from parents who were determined to do what was best for their son, and the Heisman Trophy could be Palmer's on Saturday. "I know I've been extremely fortunate in my life," Palmer said. "No matter what happens, I know my family is there for me and they always have been. That's all that matters."

|